A Love Letter from 1981

One of the basic facts of being human is this: God's creation, earth and human, belongs to us all.

From the Archives: In this unpublished article, written in 1981, Passionist priest Austin Smith (1928—2011) was drawing on nearly three decades spent living a monastic life in Toxteth, a Liverpool community oppressed by poverty and systemic racism.

With thanks to the Passionist Archives at Douai Abbey for preserving Austin’s books, articles, letters and other writings.

One of the basic facts of being human, that relates to all of us in our common humanity, is this: God's creation, earth and human, belongs to us all.

To be sure, we are all forced into delegating some people to care for it at various levels. But creation does belong to us all. God gave it to us. If we do delegate others to look after it, they remain accountable to us all. If some decide selfishly to snatch creation to themselves, to manipulate it in the cause of their own interests, we must be as stern with them as we seem to be, for example, with warring despots.

Common ownership is a fact of our human being and becoming. Common ownership must be the starting point, the conversation starter, in all our political, economic, social and cultural relationships. We may debate interpretations of it; but we must come back to it.

Common ownership of the earth and the human story is not a political programme: it is a necessary beginning. It is where one joins the caravan of the human journey. And, in the name of human fulfilment, I would suggest, it is the beginnings of wisdom. The God-given fact of common ownership was part of the original vision. Lose this, and we lose ourselves.

Common ownership has deeper spiritual implications than stocks and shares and property and profits. It is a conviction about human equality.

To be sure, like all good ideas, common ownership can go wrong—has gone wrong. But that's the predictable fulfilment, I would think, of an old tag: “the worst corruption is the corruption of the best”.

Through the past 28 years in inner-city Liverpool and, simultaneously, being a chaplain in a Prison for ten of those years, I have seen and been part of many good things happening; I have witnessed many creative awakenings, due to the perseverance of local people. I have also seen, even talked with, many who walk in the high places of our national administration. There have been seminars, home and away; meetings way beyond AOB into the night, breaking up into small groups and the expert use of ink-saturated flip-charts. It would be hard, even impossible, to list the wonderful people who have rallied to the essential summons: to ‘empower’ the people, and to be empowered.

But I have also regularly been reminded of the need for ‘practicality’: statements like, “Now let's be realistic…” And I have always been haunted, often depressed, by a strange and very unrealistic, unpractical, question: is anyone holding any seminars on disempowering 'the others'?

There's never been, as far as I know, an effect without a cause. And the powerless with whom I have dwelt and dwell are certainly not, at a radical level, the cause of their own problems. The marginalised, the insecure, the stigmatised, the powerless do not choose their way of life. It is the social and political consequence of the society they inhabit.

The powerless are not a problem; they are a question to the rest of society.

If we are intent upon changing their situation, we need to analyse the present state of society in the light of the powerless. How has this society come about? If ‘welfare’ is such an issue, what made welfare necessary? If it must go, then demands must be made of other sectors of society.

Besides, ‘problems’, especially in very secure sectors of society, are destined to be excluded. Stereotype any group in society as a ‘problem’ and exclusion is the consequence. But if one accepts the fact that we have a question here about the values of our society, one is called to reflection. If that reflection is honest and true and just, then the ‘question’ (by which I mean, the marginalised group) is included in the reflection and, hopefully, in the subsequent action. And here, I dare suggest, is wisdom.

‘Care’ can take place without liberation. I can care for the broken and powerless, at large, in society without altering my inherited values to any great degree. True wisdom only comes about when the intellect and the will, when reason and emotions, make common cause in the name of a new communion, or in other words, a new 'wholeness' with others. The liberation of the powerless is the liberation of us all.

We can only be authentic human beings, when we grasp the fact that we must become a different and new world. We cannot allow ourselves to be frozen in past concepts or patterns of thought. The philosophy of repetitionism is the road to social suicide. Any political party can find a 'newness' within itself. That is to say a political party can forge new alliances, adapt a new language, make strong statements to and about itself. But the newness I have in mind really does not concern the identity or profile of a party. One is asking for a journey much deeper than that.

When I used the term 'ownership' I had in mind neither the nationalisation of the past nor the commitment to private ownership. It is a much deeper matter. It concerns the questions: “How are all to be included in our present journey? How are the privileged of this world to reassess their states and roles and obligations? What is a new ‘wholeness’ going to look like?”

—Fr Austin Smith C.P., Liverpool 1981

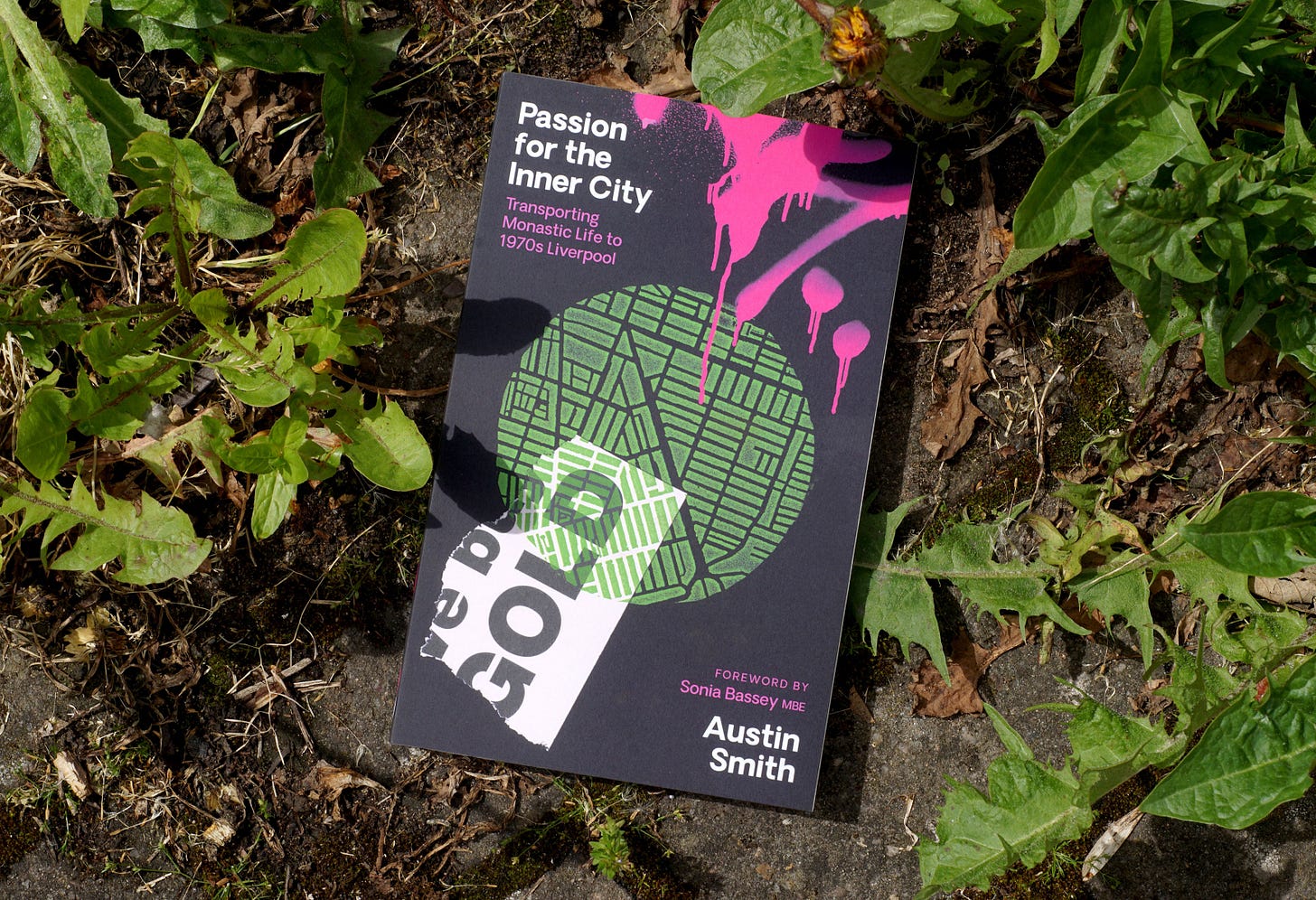

To read more from Austin, pick up a copy of Passion for the Inner City at the links below. Originally written in 1983, Passion was reworked and republished by the Passionist book imprint Lab/ora Press in 2022.

“A must-read for Christian disciples, justice activists and new monastics.” —Rev Dr Ash Barker

Paperback: Waterstones | Blackwells | Book Depository | Foyles

eBook: Kindle Store | Kobo Store