Friendship at the happy end of time

Ulterior Lives: A reminder of the necessary joy that animates all our efforts and theories of change.

Part 4 of our Ulterior Lives series: A Slow Research Project into The Outsider Politics of Monasticism. Read the introduction here.

I've begun these explorations into Jerome's account of the first hermit The Life of Saint Paul of Thebes with very material questions about how (and why) a person lives alone in a cave for many years, and how their relationship with nature might be transformed by this wilful act of uncivilisation.

I find myself wanting to write about something else now. I'm not sure how it fits into a research project into the political economy of monasticism, but I have some intuition that it does. I can’t not write about it, because it rings with such clarity, complexity and depth, even in such a short text.

The theme is friendship. I've rarely read about such a beautiful and merry mutuality as that between the old Saints Paul and Anthony. It's too vivid not to be important.

The tale begins with an intrusive thought:

“As Anthony himself would tell, there came suddenly into his mind the thought that no better monk than he had his dwelling in the desert.”

On reading this, I imagined that I was about to witness a comedy of monks competing for the crown of supreme humility; an Aesop’s fable about hidden pride. What actually ensues is a beautiful portrait of two old friends who never met until the day before they would be separated by death.

When Paul, in his cave, sees Anthony coming, he swings the door shut to preserve his century of solitude. But Anthony persuades him, saying he'll lay down and die on the doorstep if Paul won't let him in, and then Paul will have the bother of burying him.

It’s all mirth and tenderness from here. Paul welcomes Anthony with jests about his morbid entrance. They embrace, they kiss, they share prayers. They sit together and take council. Paul wishes to learn from Anthony whatever he can about the old world he abandoned. He makes more jokes about his scraggly appearance. When the crow delivers them a loaf of bread for supper they argue over who should break it, each preferring the other, until they finally agree to pull it from each end like a Christmas cracker. Then they eat and spend the night together in vigil.

There is some feeling of magical completeness about the scene, something eschatological: two old friends stood together at the unexpectedly happy end of time. It reminds me of Tolkien's eucatastrophe. It’s as though two people faithfully carried the same secret all their lives until they finally found each other… as though the question implicit in years of solitude were finally answered.

I have a feeling that without this secret fire that glows between creatures, the best of things ring hollow. Theories of change, alternative economies, rules for life, simplicity, justice, perfection; all these feel dry and void without friendship and affection as the crown at the end of all things; this undefended and joyous togetherness.

I cannot live without putting my feet in this river, in a world where archaic texts have much to say about the individual's pursuit of perfection, and where the interests of the present are often preoccupied with paths of self-actualisation and dry formulas of social and political transformation. Even in the earliest tales of the most severe and solitary hermits, friendship remains the best of things, the common meaning of any life well-lived and the reconciling joy at the end of the world.

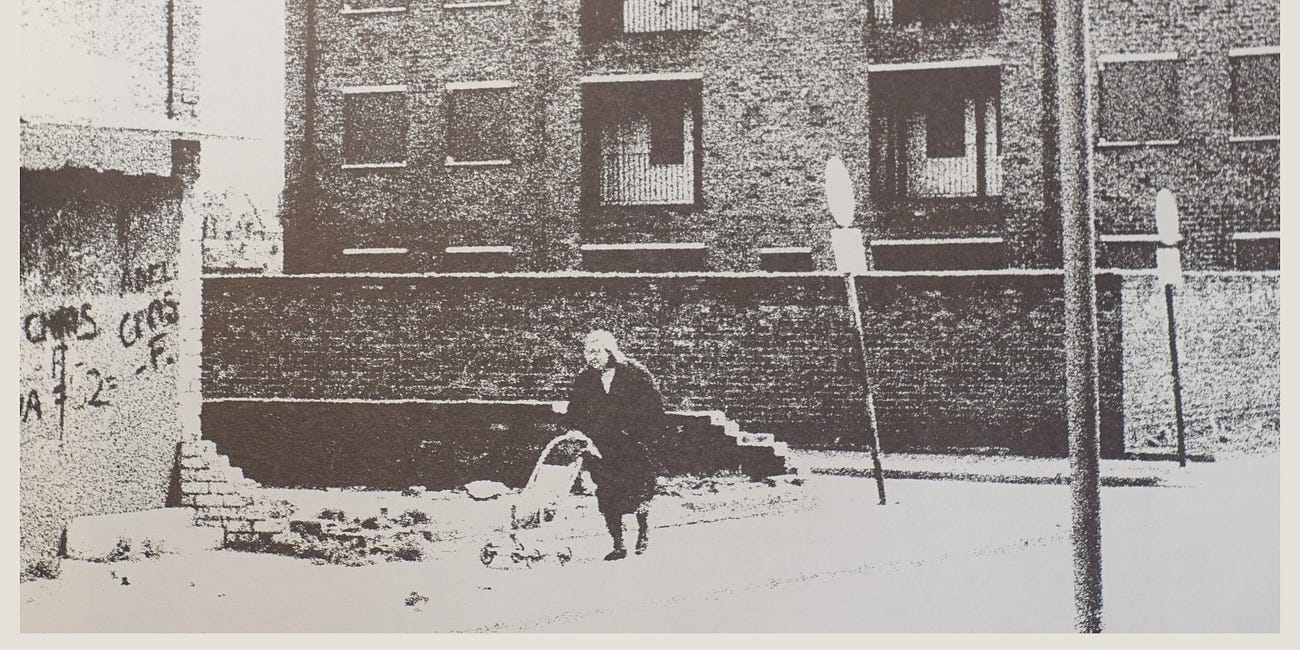

A Love Letter from 1981

"Common ownership must be the starting point, the conversation starter." Three decades of inner-city monastic life in Toxteth, a Liverpool community oppressed by poverty and systemic racism.

This slow research project is supported by the Passionists, a Catholic religious order committed to works of solidarity with suffering people and the suffering creation, founded in 1720. You can read our previous series exploring Passionist writings here, or find out more about the modern-day order on their website.

I wonder we have friendship with the son of god and I am wondering whether we truly realise it in this day and age where separation and independence can take centre stage what being a friend can mean thanks for sharing the thought of monks in a different age and hope we can all rise to the reality facing us