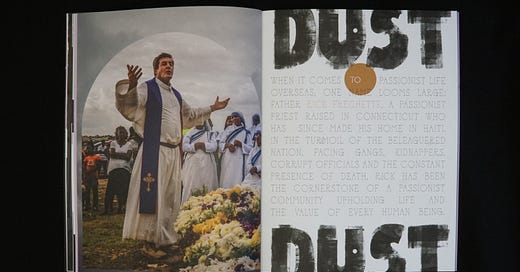

Dust to Dust: Passionist Life in Haiti

Facing gangs, kidnappers, corrupt officials and the constant presence of death, Rick Frechette and the Passionist community fight to uphold the value of every human being.

From Passio Magazine #12 — buy the print edition here

When it comes to Passionist life overseas, one name looms large: Father Rick Frechette, a Passionist priest raised in Connecticut who has since made his home in Haiti. In the complete turmoil of the beleaguered nation, facing gangs, kidnappers, corrupt officials and the constant presence of death, Rick has been the cornerstone of a Passionist community upholding life and the value of every human being there. Although the phrase ‘hard pressed on every side’ comes to mind, Rick found a moment of quiet to respond to our questions.

The following is adapted from our communication as well as previous letters to supporters where Rick has eloquently shared his thoughts and anecdotes.

Two hours in dark scrublands, driving on semblances of dirt roads. It is 10pm. Father Rick, with his companions Daniel and Raphael, approach a crossroads. A crowd of thirty people are standing and waiting, many of them carrying military-grade weapons.

Two weeks ago, a priest, Father Marcel, was kidnapped, along with his driver and three Church women. Tonight, a release deal has been cut by their families, a ransom paid; Rick has been led to this spot by bandits as the ‘guarantor’ that the payment will be honoured, although there is not much ‘guaranteed’ about it.

It’s easy to spot the people they’re looking for, huddled under a mango tree. It’s not their colour or clothing that gives them away; it’s the demeanour, the posture of defeat, while those around them stand proud and arrogant. They embody Psalm 129, Rick thinks to himself: de profundis, the depths. Out of the depths I cry to you, O Lord.

There’s no way of knowing how this moment will play out. Whether the deal will be honoured. Whether Rick and his companions will be killed, or taken for their kidnapping value. Whether they will be duped and given any five people, those deemed not worth the bullets. They don’t know the faces of the people they are there to rescue; only the name of the priest. “I cannot pretend these visits are not unnerving,” Rick says: their lives in the hands of angry teenagers clutching weapons bigger than they are.

This time, at least, the exchange happens as intended. Their Toyota ambulance almost comically struggles away—below 20mph. Because of fuel shortages and illegal markets, it’s likely the diesel in the ambulance engine has been cut with water.

Negotiating with kidnappers, it turns out, is now a regular part of Rick’s duties as a polymath Passionist priest living in Port-au-Prince, Haiti. Although it’s not a responsibility he would have chosen, he doesn’t struggle to cite precedents for it: Popes who met and negotiated with barbarians outside the city; South American bishops who met with drug dealers and traffickers to steer their power in more humane directions. “Jesus spoke with Satan more than once,” he adds memorably. “Even instructed him in proper understanding of scripture.”

“To be speaking anything humanitarian to the very ones who are trashing humanity, blows your mind,” he writes later. “It’s totally impossible to keep your equilibrium unless you feel a deep calling, even divine mandate, to work for life, life fully and always.” And there is another of Jesus’ sayings that sits at the forefront of Fr Rick’s mind: “His will that not even one be lost.” More than a few times, they have even coaxed one of these armed teenagers away into a better life.

Back at the Passionist house, Father Marcel and the others stay for the night. The meal, showers and clean linen surely feel like a gift quite literally from God.

Marcel joins the 6.30 morning prayers, the Canticle of Zechariah: the dawn from on high shall break upon us, to shine on those who dwell in darkness and the shadow of death, and to guide our feet into the way of peace. He hesitatingly accepts to lead the Mass afterwards; raising the bread with still shaking hands, eyes startling at any loud noise from outside the chapel. For Haiti’s priests, PTSD is a very real consequence of their calling. So many of the victims of kidnapping, as Rick puts it, “were never freed interiorly. Releasing them from captivity was not a happy ending, but rather the beginning of living out a long and terrible inner bondage.”

On the night of this rescue, in the van, Father Marcel had given thanks for the group’s liberation; and he had prayed, too, for those who had beaten him repeatedly, for the kidnap victims still there, and those who had already been killed. Rick calls this participating in “the ancient teachings by which we are healed and regain some balance during the long lent of life.

“We pray, starting with praise, followed by thanksgiving, and finally presenting our anguishes to God in prayer. For a stronger dose of this spiritual medicine, let your first prayer be for your enemies.”

is there a deadline? Father Rick writes to me with unpunctuated haste. we have been managing gang assaults in our area.

Getting to grips with Rick’s inner world is an exercise in humility. We’ve agreed to communicate by email as video is problematic for him. I send questions and think they look hopelessly trite; Rick has to put off his responses more than once, to put out fires both metaphorical and, probably, literal. When he does write, it’s simultaneously unvarnished and poetic.

Life in Haiti is difficult to contemplate, overwhelming to get your head around. Rick is not bashful about it: “Haiti is a failed state,” he writes. “Run by gangs, corrupt on every level. It is an ecological disaster, an economic failure, a culture in shambles. It is a place to run from.” He says life under gang rule brings the term ‘howling wasteland’ to mind. Elsewhere, he simply calls it Calvary—the place of the skull; a fitting place, he notes, for the people of Good Friday to enter.

Father Rick arrived in 1987, just after the fall of the dictator Jean Claude Duvalier. “I stepped from opulent suburbs in the USA into a shocking world where small babies and children were dying of starvation, and looked like they had already lived a century,” Rick writes to me. “I witnessed the death of children of all ages in volumes more than I care to relate.”

In many parts of the wider world, it was a time of great change and positivity; but Haiti, even then, was incredibly poor, the poorest country in the Southern hemisphere. And then, too, it was tumultuous and violent. A dozen coup d’etats followed in Rick’s first two years in the country. Although shocked, Rick was seemingly undeterred.

“I was 34; young and healthy, enthused and full of energy,” he explains. “It’s right to be these things when you are young. Without this youthful exuberance there would be no incentive to fight the unbeatable foe, and be convinced you could win.”

The exuberance certainly kept Rick fuelled for some time. When the New York Times crossed paths with him in 2017, they remarked he “seems like seven people in one—each divergent skill emerging from necessity because there was no-one else to do it.” His first role, with the charity Nuestros Pequeños Hermanos, had been to establish an orphanage. Then—since so many of the children required medical attention that nobody could provide—he studied to become a doctor at age 40.

On his return, the grown-up orphans, accompanying him on medical rounds through the slums, proposed the idea for the St Luke’s Foundation—which has now built, and still runs, 34 schools. There is an adult hospital, too; a school for disabled children; and a seemingly endless list of social enterprises where Father Rick served as entrepreneur, handyman, and mentor, in between his duties as a priest.

These projects have unfolded across 35 years that have been “cruel and unrelenting” to the country. Hurricanes, earthquakes, flash floods, fires. Disastrous diseases like HIV, malaria, Covid: currently, cholera. Violent, repeated political upheaval. The proliferation of drugs, guns, crime and gangs. Even the ecological damage, spreading from the cities, has been drastic—tropical gardens replaced by filth and garbage.

“On top of all the poverties, you can add the increasing poverty of imagination,” Rick writes. “The ability to even imagine anything different. The average Haitian has never seen anything honest, clean, well organised, functional. Many have never seen a flower.”

“The inner work of nurturing compassion against burnout is long and hard. You cannot let your guard down at all.”

Now 70, Rick is no less devoted to Haiti. It is clear by this point that nothing will make him leave. He carries a deeply wounded love for the place; it is already long established that he is giving his life for it. That doesn’t mean, however, that it is easy in any sense. “The inner work of nurturing compassion against burnout is long and hard,” he says pointedly. “And there is no guarantee. You cannot let your guard down at all.”

During my correspondence to Rick, the community is rocked by the death of Raphael Louigene, a ‘beloved Son’ to Rick—“one of the pillars of our mission, one of the founders, one of our most able leaders.” Raphael suffered a lethal stroke, which Rick attributes to “the stress of his burdens—burdens he gladly carried for the countless vulnerable and suffering.” Raphel had been, by all accounts, a local hero, beloved by all; having worked with Rick from the age of 17, he almost represented a monument to what Haiti could be.

The grief is still new, and palpable. Rick often tried to convince Raphael to move to the USA; he would respond, what would become of Haiti if everyone left? After his death, “when we travelled through violent gangs to visit his mother in the province, we passed through dangerous areas with no problem because these gangs were also grieving Raphael, for all his humanitarian efforts in their areas.”

Rick’s eulogy to his treasured friend is effusive and moving, and then the mourning segues into resolve: “I assure you that in obedience to God’s dream for humanity, for the world, for Haiti, and strengthened by Raphael’s example, we pledge to engage even stronger to be in solidarity with the people in such difficult times, fully convinced that we will see better times ahead with God’s help.” This is what a pugilistic hope looks like.

It is Ash Wednesday, 2022. Father Rick celebrates mass early in the morning. A message arrives at the chapel that a charred car has been found near to their school gate. Within it, a body burned to ashes.

Along with some companions, Rick heads to the horrific scene in order to pray for the dead. Minds distracted, words stumbling, still dressed in alb and stole, “armed only with the psalms,” they raise their hands in blessing over the unidentifiable body. The Lenten ashes linger on their own foreheads, while they look straight at the brutal reality that you are dust, and unto dust you shall return. Onlookers are either horrified or amused by their efforts.

In most cases, that would be the end of the story; so many Haitians die in anonymity. Burying the abandoned dead has become a huge part of St Luke’s operation, even though the piles of bodies in the morgue and the street are more than they could possibly hope to attend to. Rick and others pick them up anyway, to take them out of the view of children, away from hungry pigs and dogs, to bury them with some semblance of dignity even if they never know their names. They bury them in coffins made from cardboard on wooden frames, sealed with sellotape. On All Souls’ Day—also the second day of a Haitian festival for the dead—St Luke’s usually oversees a Catholic service at their cemetery, honouring the tens of thousands of unmarked graves.

The men clearing the bodies grew up in poverty, intimately familiar with death in a way that the West has forgotten about. They know any of these bodies could have been them. In the Ash Wednesday story, though, it becomes more real. They learn the name of the person in the car: Yvon, a brother to somebody they already know.

“It became personal,” Rick relayed. “Talking to Yvon’s brother on the phone. Receiving a picture of Yvon’s smiling face. The dry bones and ashes of Ezekiel’s valley suddenly took on flesh. Yvon arose from ashes and became real to us. It was like a stomach punch.”

The stomach punch, the grief, is a necessary medicine in the battle against dehumanisation. To keep their heads above water, they can’t afford to stop believing in the value of humanity.

While Rick doesn’t spare much breath for the oft-asked question whether his faith has suffered from witnessing all this suffering—gallows humour helps, he says, but not half as much as his constant prayer—more interesting to witness is Rick’s faith in people. “I used to answer the faith question by saying that I have more trouble believing in people. But I hesitate to say that now, even though people are without any doubt the cause of most of the horrors we’ve seen.”

It comes down to what Rick calls the magnificent equation: “We believe in God. God believes in us.” He echoes the stories, in Scripture and elsewhere, that suggest a handful of good people can save the world: “There is also the persistent idea that you won’t know who they are. They are humble, reverent, hardworking, good and anonymous. I noticed that every time I am ready to condemn the human race, someone else wonderful shows up.”

“While bandits and fires can destroy a building, they cannot destroy faith, or meaning, or worship. They cannot destroy hope.”

Rick’s missives to his supporters put me most in mind, frankly, of the Epistles; they overflow with the sorrowful happenings of the world, Rick’s evident broken-heartedness, and his brutally hard-won hope. Like the writers of those scriptural Letters, or indeed the Psalms, once he has listed the despair and the horror he seems compelled to turn his gaze upwards and end with his hopes, his dreams, the greater Wisdom.

In other hands, it might feel trite. In the West, certainly, we have had our fair share of preachers paving over distress with self-help platitudes. Father Rick, on the other hand, bears on his body (and his mind) the scars that show he belongs to Jesus: it is hard to doubt he means it with his very being.

Only a few months after Ash Wednesday, fires break out across Port-au-Prince. One of the buildings destroyed is the interim Cathedral (the original Cathedral, above, still lies in ruins from the 2010 earthquake). Rick walks through the burned Cathedral, charred sacred artefacts crunching under his boots, wondering how they will celebrate Our Lady of the Assumption’s feast day just a few weeks later.

Yet hundreds still gather for daily mass in the shadow of the burned cathedral, risking the threat of war-time weaponry. The priests of the Cathedral do not abandon their people, either. “While bandits and fires can destroy a building, they cannot destroy faith, or meaning, or worship. They cannot destroy hope.” While the bandits show their complete disdain for life, the Cathedral feast—with or without a Cathedral—proclaims the high dignity of the human body.

“People are exhausted and discouraged, but our suffering shows how deeply ‘what is right’ is engrained in us. Refusing to let the sun set on our sense of right,” he concludes, “becomes the way to preserve inner freedom. We know the price that must be paid, over and over again, to do this.”

There’s no doubt that the crises keep mounting. Rick describes this moment as the worst crisis they have ever faced in 36 years, the institutions of civilization disintegrating. Many Haitian citizens are falling into deep despair: more recently, citizens sick of the fear and the gang rule have turned to vigilante justice, lashing out with brutal violence at both gang members and police oppressing their communities.

Rick, as always, shows a sanguine side. “At 34, I was a Passionist on a high horse, a victory horse,” Rick shares. “I was a Passionist who lived as if Good Friday was overdone, nowhere near as bad as thought.

“Here I am at 70. Healthy and strong, still enthused and full of energy; but a different kind of energy. My high horse is out to pasture, retired, suffering the heat and sparseness caused by global ecological crisis.”

“I still have my feet, my heart, my mind, on the place of the skull. Like everyone else my hope is assaulted. Much better said, we are here, at the place of the skull. Eleven million people.

“I take my small place with this precious people of God. We hold each other up, by dreaming a united dream for a better world, by working for this better world in God’s image and likeness, by daring to speak of God before the unspeakable. We quicken each other by our relentless faith and small and continuous acts of heroism.

“I don’t dare now to think of Good Friday as overrated. On our worst days, I more fear it will never end. But I know most certainly that if not for the gracious and constant help of the Crucified One, I would not last five seconds more as a son of St Paul of the Cross. And yet a son of Paul of the Cross I feel so privileged to be.”

Chris Donald is part of the Passio Media team. @chris.makes.things

ILLUMINATE Episode 01 — Sean Goan

Illuminate is a new video series of short-form interviews, discussing what we can glean from thousands of years of spiritual wisdom, and 300 years of Passionist spirituality in particular.

Watch the first episode, with Biblical scholar Sean Goan, here.

More for November 2023

Join our Passionist Partners, Green Christian, at their Annual Members Meeting on Sat 11th November in London; exploring the theme, 'Where is the Hope?', it's a great opportunity to gather with like minds and find ways to respond prayerfully/hopefully to the times.

As we witness the escalating violence in Gaza—and for anyone who may have felt at a loss with where to start—Quakers in Britain have 5 actions of solidarity you can take right away.

You can also join climate vigils and protests around the country being organised through Christian Climate Action — outside bank branches, oil companies, cathedrals and more. These are peaceful and deeply prayerful events, and open to anyone.