Talking to a 21st Century hermit

An unexpected conversation with Rachel Denton, the canonical hermit of the Diocese of Hallam.

Hello to recent subscribers! We’ll have more from our new Ulterior Lives series next week. This post below is an updated article from the most recent issue of Passio Magazine, our limited print edition which comes out twice a year. You can order a copy, and most back-issues, in our shop.

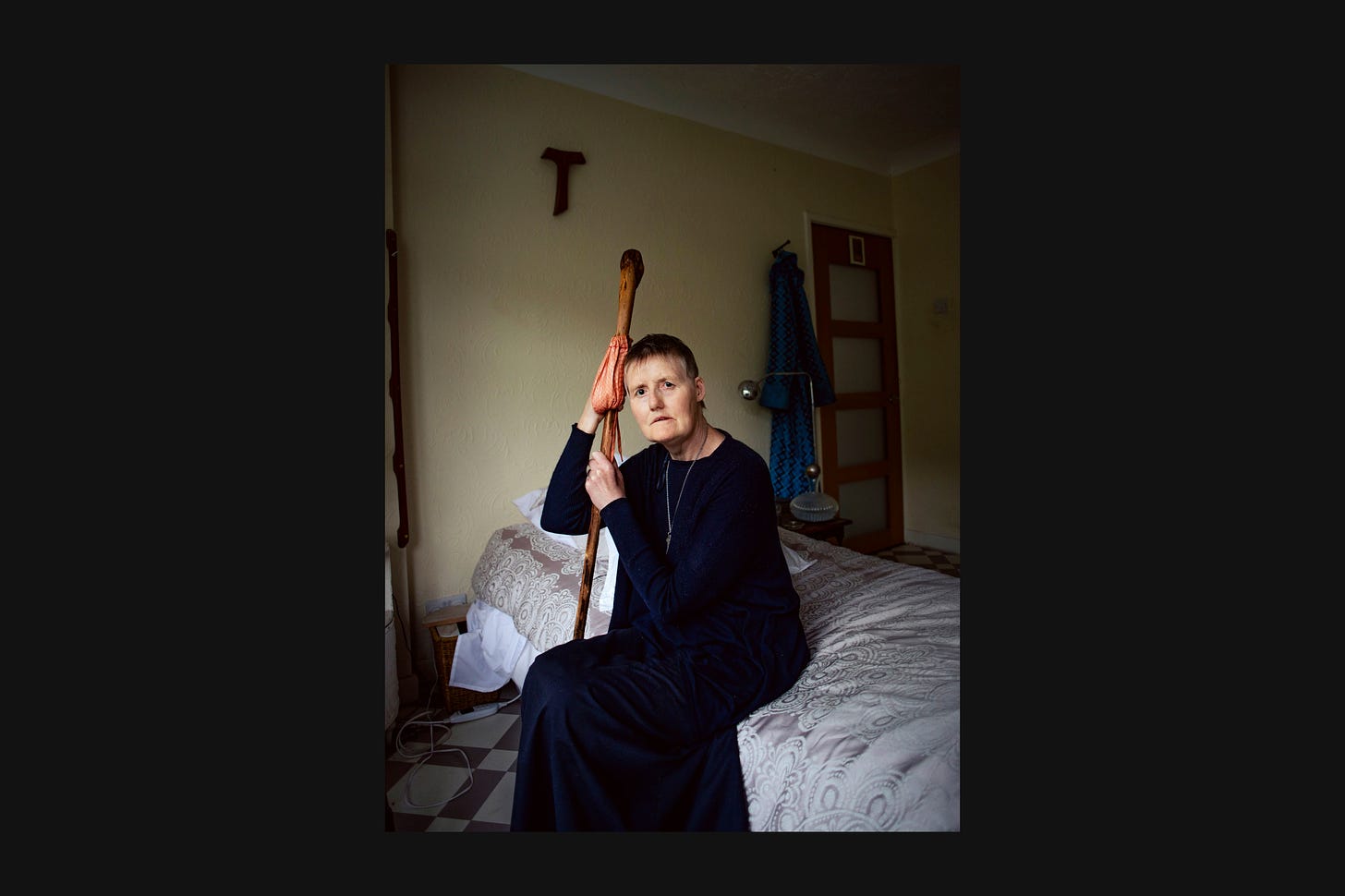

“Hermits are just people,” Rachel Denton tells me. “Many people are interested in what you wear, what you eat, your ‘cave’. And they’re very disappointed, of course,” she adds offhandedly. “I always sense that once people realise we look fairly ordinary and we talk fairly ordinarily, they’re not so interested. They would like us to be curiosities.”

I can admit that it was sheer curiosity that caused me to grab the opportunity to talk to Rachel, the ‘canonical’ hermit of the Diocese of Hallam. In the last few years I’ve talked to many people in vowed religious life, more than I ever have before. Having found my own form of faith in a house church, I am irreverent to a fault, and instinctively non-hierarchical about almost everything. That is, I don’t come to these conversations with some sense of holy awe. But equally, I’m intrigued by anyone who is genuinely living an unconventional life, so far off the beaten track that nobody even notices. I try to leave my expectations at the door and understand them on their terms.

Talking to Rachel does upend my main preconception though: I am interested with what a ‘verified’ hermit has to say about the experience of simple living. (It seems a given that the era of economic growth for the West is coming to an end—to put it mildly—and I’ll take any wisdom I can get from those already living out a real simplicity of life). For about 20 years, Rachel was living at St Cuthbert’s House, an old cottage some way outside Sheffield; despite her protestations of normality, she did in fact exemplify a form of ascetic life. The home was modest to the point of austere, her wardrobe limited, and she grew much of her own food, living sustainably off the land as much as was possible.

Time and disability, however, has meant that she’s recently made a move further into the city, for easier access to the hospital. The simplicity is still there for the most part, but we end up talking instead about that life change: what happens to our faith and spirituality when the internal circumstances of our own bodies shifts, and how that looks in a life built on solitude and prayer.

As Rachel admits herself, when in conversation with a hermit, the words all start rushing out.

“Most people are curious about the solitude and the silence. But there are others who are attracted by the sense of quiet, and the sense of contentment. Most hermits are content. I think most people in the contemplative life are content—because they’ve chosen it. Yes, we give up things; but most of us want it, and most of us like it.”

Rachel’s aunt had been a nun, and the life appealed to her from an early age. She became a Carmelite nun herself, aged 23; the Carmelite Order has a focus on solitude, “but life was so tightly structured, I felt it was hard to find the time to be alone.” Finding it claustrophobic, she agonised over the decision to leave. “Kneeling there, if I’m honest, I’m believing it’s God’s will that I stay. It’s certainly the community’s will. In the end I said, look, if you’re anything like the God I believe you to be, if I walk away, I think you’ll still be there when I get out. That was a turning point in my relationship with God, because God had done something that I wanted.”

Thinking that was the end of that, she trained as a science teacher, and became a special needs coordinator and a deputy head teacher. “But I never felt truly content,” she adds. “I’d always had this romantic idea of living alone, with nothing to do but grow my own fruit and vegetables and pray. I’d recently moved schools, and wasn’t happy. I would sit and close my eyes for 20 or so minutes at lunchtime, so I could feel apart and alone. I realised if I didn’t do it then, I never would.” She considers herself fortunate to have found a spot to live, with enough of a garden to grow food; less of a feat twenty years ago, perhaps, but in fairness the soon-to-be-St Cuthbert’s House still required a lot of work to be liveable. Rachel undertook it steadily.

The process to be an officially recognised ‘hermit’ in the church (which doesn’t come with any kind of support, pastoral or financial) requires the applicant to write their own ‘rule of life’. Rachel’s is short, and “flexible, realistic”. It describes her aspiration for the life of the hermitage “to be a life of thanksgiving,” done “for the sake of the church”, and likens it to the times Jesus drew away to pray.

She pledged to live simply, in solitude and silence— “Like somebody who returns to their family after they’ve done something they have to do. With a young family, there’s a sense of isolation from the world: because there just isn’t any time in the day, it’s all devoted to caring for these youngsters. I’m very impressed by the way people give their life over completely. So for me, I do things outside the home, but every moment I’m not, I’ll be at home in solitude and silence.”

The other parts of the rule are: to work towards self-sufficient living, sharing any excess with those who are worse off. And lastly, to spend time each day in prayer. “I don’t do the whole Office, or Mass, or something. Just spend time each day.”

“Hermitage is ordinary; it’s not about grand visions, just about why you’re doing it. It’s simply taking the opportunity to focus intently on the ordinary, to find the space and the quiet to be grateful for it, and to recognise God in that.” She stresses that she sees her own commitment to solitude as a commitment to the wider community as well. “It’s not a prayer intercession factory. That’s not the daily task. But there’s a sense of responsibility in it, towards the whole church. I don’t do this on behalf of the church, but I do it as the church; the church is present in the hermitage with me.”

This was the pattern for 21 or so years—until bad health intervened. “For a long time, my disabilities have been inconveniences rather than tragedies. I haven’t been in much pain. It limited what I was able to do, but that was okay. It meant I took more time over things, but I looked on it more as a tool of experiencing poverty, if you like. I never really felt out of control—until this last winter.”

“The visual poverty of my circumstances has changed compared to my early years. What I can do to survive has changed. There’s a different kind of poverty now. There’s a poverty to do with my disability; there’s a lot that I can’t achieve, and a lot that’s inaccessible to me. It was a shock.” If intention was the difference between hermitage and just ‘living alone’, then illness marked a different era, a limitation and a suffering that she hadn’t willingly chosen.

When her neurological problems grew worse, “I found that prayer became simply bearing with the moment,” she says. “It wasn’t particularly ‘companionship’ or conversation with God. It wasn’t any sense of God. You could say it was faith, but it didn’t feel like faith; it just felt like, this is God as well. Did I feel God with me? No. Did I shout at God a lot? Yes. Did I have comfort from God?” She trails off for a moment. “Quite possibly, because I never considered God wasn’t in it. But there was no sense of God being in it.”

I guess Rachel was right and I was expecting a ‘curiosity’ in the hermit’s cave. I think a selfish part of me was disappointed at the ordinariness of this experience, that I couldn’t get some second-hand revelatory secret from Rachel’s twenty years of prayer practice. But I wasn’t sorry for the conversation. In fact I was honoured that she spoke very candidly to me about her struggles, and we spoke about the difficulties in my own life, too. Maybe the benefit was to walk outside the city walls, out of the flimsy man-made environment, up to the hermit’s cave; and to see my humanity and frailness reflected back, out in the quiet and the wildness of the real world.

Beyond that particular bout of illness, Rachel is reflective. “When I had the energy to look again, after being ill, still God is there,” she insists. “And I do find it wonderful.”

The change, for Rachel, has been that sitting in prayerful silence feels more real to her than trying to read the daily office. I was never a part of the traditions of liturgy and office myself: but I have been in many spaces where long, seemingly passionate and verbose prayers were prized over silence; where petition is the only mode of conversation we know. “It’s an odd thing for a solitary person to do, to say a whole lot of words, and to say that God likes that better than me just sitting there,” Rachel puts it.

“The feeling of prayerful silence feels real. I suspect that God, in creating us and loving us, didn’t intend us to be making an effort all the time,” she adds, smiling. “In our relationships, there are times we really need to be intentional and sit down and work hard at communicating with each other. But there’s also moments when you sit down and have a nice meal together, and don’t think about it—you just enjoy it. I feel like my relationship with God has settled into this sort of, this is just what we are. God and I are much more relaxed together.

“I now try to share a different story about God, and that’s the God who has always been human. The Word in the beginning was God. To be human is part of God’s nature. Jesus of Nazareth being born is a moment in time where Jesus enters into God’s own humanity, certainly. He becomes human in history. But as John Duns Scotus says, there was no ‘Plan B’. God was always going to be Jesus, and that’s because God is human.

“It changes the story about God. Because our humanity is not that we are trying to be divine. It’s that our humanity is God’s humanity, and therefore it’s enough. We don’t need to be this superhuman thing. Just being human is all God wanted for us. And just being human is the best place to find God, because God is human too.”

Read more from Passio Issue 14 here.